Can people learn from nature to build tools & infrastructure that fits with nature?

Over the past 3.8 billion years, life on this planet – in all its diverse and dazzling forms – has evolved some pretty spectacular ways to thrive in even the most challenging conditions.

The Namib desert beetle survives in one of the world’s harshest deserts by . Termite mounds are intricately structured, self-regulating labyrinths that attune to their environment to optimise air circulation and maintain remarkably cool and consistent interior temperatures no matter how hot or cold it gets outside. Communities of microbes in the soil band together to suppress harmful pathogens.

This is what Janine Benyus, co-founder of the Biomimicry Institute, a non-profit organisation based in the United States, calls, the ‘genius of nature.’

Founded in 2006, the Biomimicry Institute focuses on educating people about nature’s genius and advocating to make biomimicry thinking a mainstream practice in schools, businesses and communities. The Institute runs programs in schools, museums, and aquariums across the United States, and also mounts design challenges to galvanize innovation in particular areas such as the food system.

The Institute builds on the work of Benyus and other biomimicry pioneers who since the 1990s have been urging architects, farmers, designers businesspeople and others to learn from nature’s processes of self-regulation, diversity, efficiency and interconnectedness.

Biomimicry, Benyus argues, has huge transformative potential for the ways in which people think, learn, meet their material needs, build their communities, and exist within a greater community of life on the planet. As she likes to point out, nature has already solved many of humanity’s most pressing challenges in energy, architecture, transportation, medicine, agriculture and communication – and has solved them sustainably, without the social-ecological destruction that all too often accompanies human ingenuity.

“When we look at what is truly sustainable, the only real model that has worked over long periods of time is the natural world,” says Benyus in this TED Talk. Nature’s failed experiments become fossils, while life adapts and carries on.

All organisms – whether plant, bird, mushroom, tree, soil microbe, fish or human – have their own strategies for acquiring nutrients, water, energy and somewhere to live – as well as for communicating and keeping healthy. And it is through these these ongoing, intertwined processes of life that ecosystems create the conditions conducive to life.

As Benyus points out, while humanity is busy burning through fossil fuel stores accumulated over billions of years to meet its energy demands, the leaves on trees capture solar energy directly from the sun with astonishing efficiency, fuelling the life cycle of the tree and producing oxygen to regulate the atmosphere in the process.

The biomimicry practice is grounded in six key ‘life’s principles’:

- adapt to changing conditions

- be locally attuned and responsive

- use life-friendly chemistry

- be resource efficient (material and energy)

- integrate development with growth

- evolve to survive.

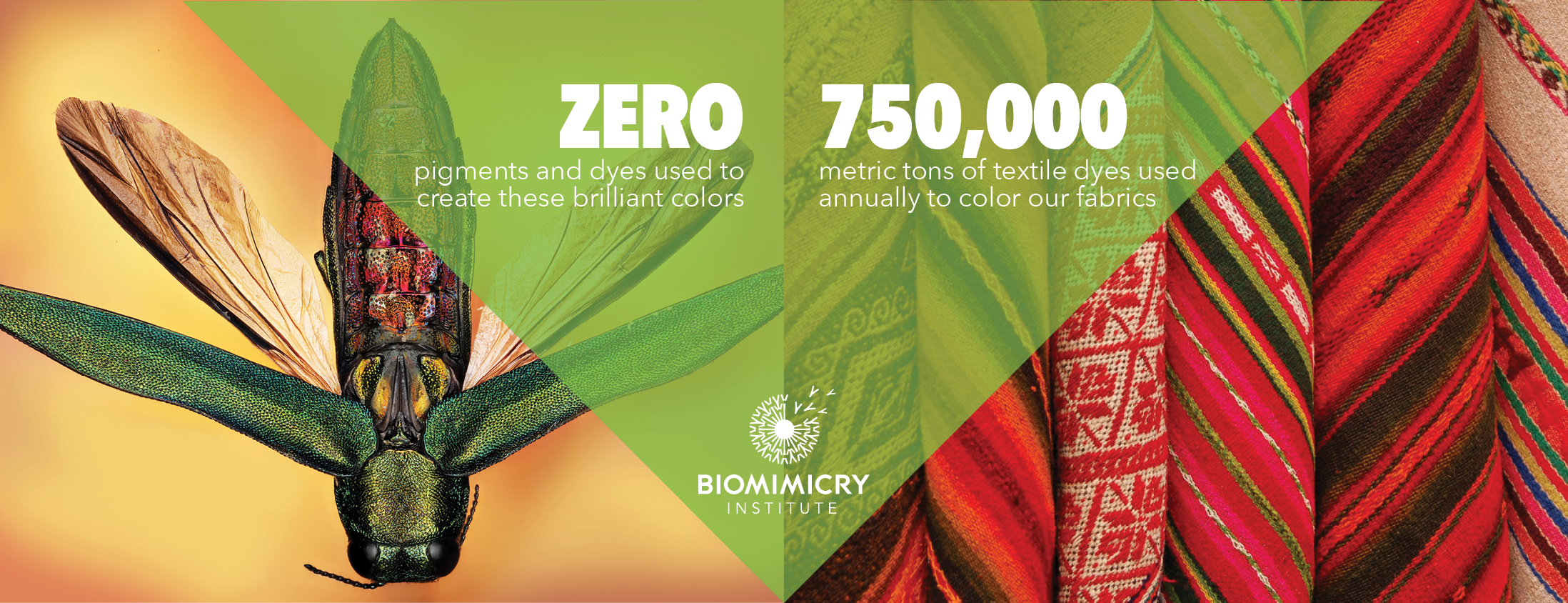

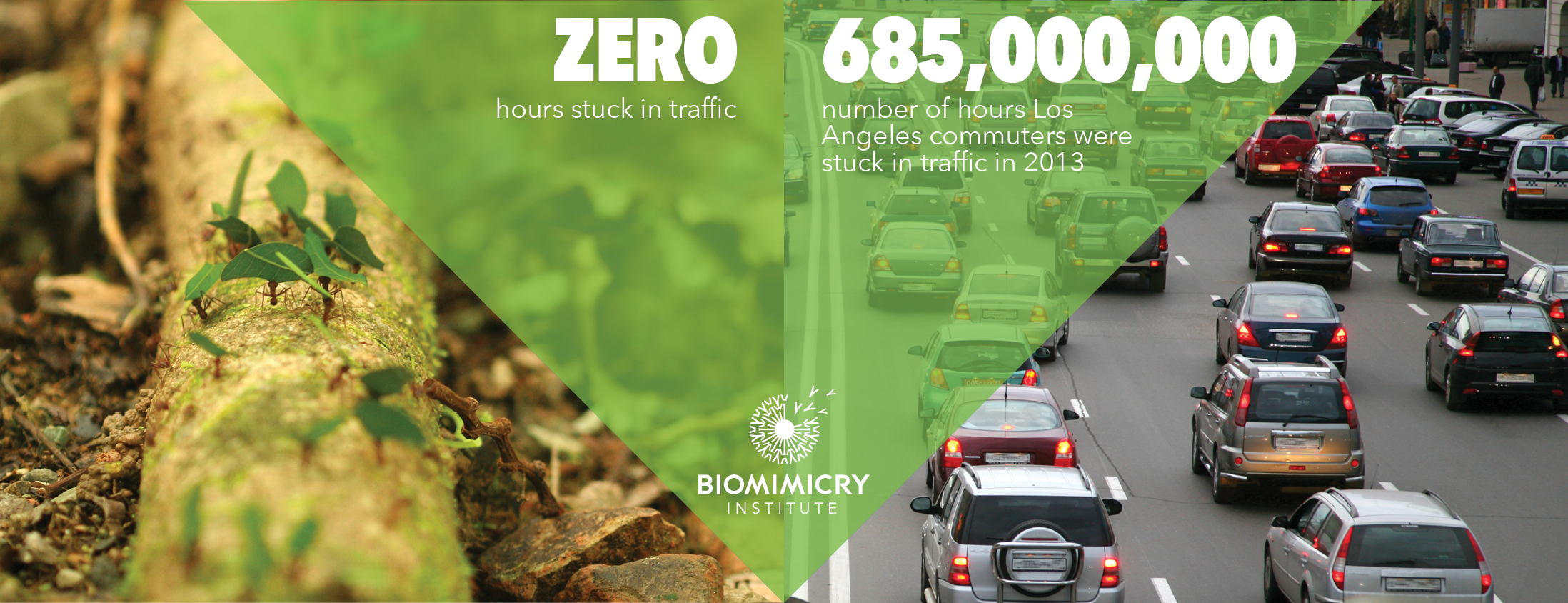

In thinking and practice, biomimicry may contribute towards social-ecological transformation in many ways. In urban planning fields, biomimicry practitioners have been studying ways of designing cities to function more like natural ecosystems, purifying air and water and regulating the local climate. In education, biomimicry is inspiring kids to become social-ecological citizens, imbued with a sense of connection to and reverence for nature, and a fascination with the endless relationships and processes expressed in nature. In the corporate world, nature’s principle of zero waste is urging professionals to rethink throwaway consumer culture.

The current and potential applications of biomimicry are vast, ranging from organisational management to urban design, from the Japanese bullet train (whose nose mimics the shape of a kingfisher’s head) to a wind turbine based on the shape of a Humpback whale’s fin.

The discovery of a dolphin’s unique ability to process sound travelling through water, and thus communicate with and distinguish the whistles of particular individuals over long distances, has led one company to develop an underwater modem to serve as an early warning system for tsunamis in the Indian Ocean. Hundreds of other examples of nature-inspired ingenuity can be found on the biomimicry websiteAsknature.org

The biomimicry movement has numerous organisational structures operating in the U.S and in 17 countries around the world. In addition to the Biomimicry Institute in the U.S. there is Biomimicry 3.8, a for-profit consultancy established by Benyus, Dayna Baumeister and Chris Allen has introduced biomimicry to corporate clients such as Boeing, Proctor & Gamble and Interface, a carpet manufacturer that overhauled its production processes in accordance with biomimicry principles.

As biomimicry becomes increasingly mainstream, however, one of its challenges will be to remain a transformative practice without becoming another form of extraction from nature. For example, many biomimicry applications so far have been developed by private companies that may be more focused bottom line profitability than on contributing toward a more just and sustainable world. While the invention of specific, discrete technologies may be ingenious, it is equally important to ask nature to share its genius with proper humility and connect these discrete interventions to a larger vision of a social-ecological community inspired by, and at the same time part of, nature’s genius.