Over half of the world’s population lives in cities, and rates of urbanization continue to increase. In the Anthropocene, cities are significant players. Dense concentrations of people and resources, while sometimes environmentally taxing, are also fertile grounds for cooperation and models of sustainability.

Melbourne, Australia started turning heads in 2015 when they put forward a simple, yet revolutionary, model for renewable energy transition. Thirteen of the largest institutions in the city (including the city government itself) put their heads together and signed an agreement to purchase their energy from a new large-scale renewable energy projects.

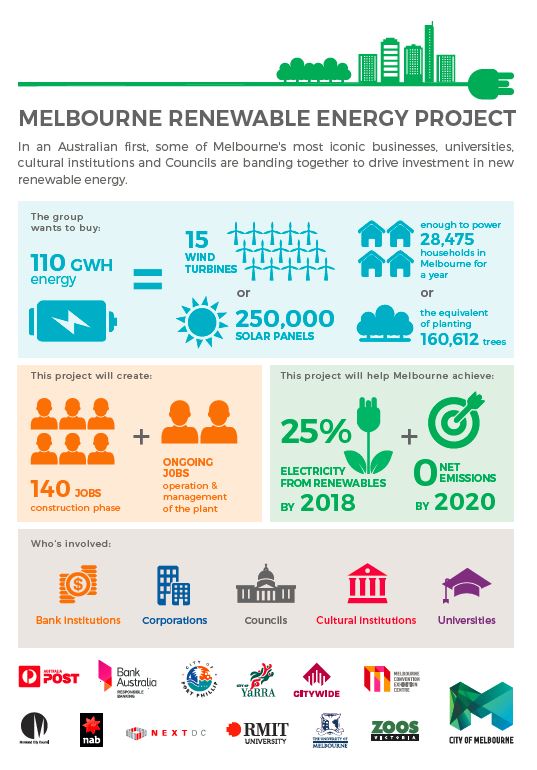

The “revolutionary” aspect of this was an unlikely partnership among prominent institutions from all over the city. Members of this consortium range from the Melbourne city government, Australia Post, National Australia Bank, and University of Melbourne, among others. This group of buyers plans on purchasing 110 GWh worth of energy from new large scale renewable energy facilities through a “group purchasing model”. A group model allows for investment at a much larger scale than any of this institutions could do on its own.

There are many benefits of this group purchasing model. Firstly, a renewable energy project of this size is predicted to offset up to 138,600 tonnes of CO2 each year. It also secures a long-term market for renewable energy production project, which is a needed step for the development of large-scale projects.

Currently, the consortium is in the process of accepting applications from potential developers. There are two successful tenders so far, both large-scale wind farms.

The most exciting aspect of this model may be its replicability. Other large cities from around the world have expressed interest in Melbourne’s model, notably members of the C40 Cities climate Leadership group, which consists of many of the world’s largest, and most influential mega-cities such as London, Beijing, Paris and New York, who are committed to addressing climate change.

In an article from last year, the Guardian referred to Melbourne’s energy plan as a ‘blue-print’ for other cities to follow. In the absence of global leadership on climate action, solutions may come from cities, through unlikely partnerships and cooperation.

Photos by Anna Kusmer; Info-graphic from City of Melbourne